|

پروفسور محمد

حسین سلطان زاده

استاد دانشگاه علوم پزشکی شهید بهشتی

متخصص کودکان ونوزادان

طی دوره بالینی عفونی از میوکلینیک آمریکا

دبیر برگزاری کنفرانس های ماهیانه گروه اطفال

دانشگاه علوم پزشکی شهید بهشتی

|

معرفی : دکتر

شاداب صالح پور

فوق تخصص غدد اطفال

به اتفاق اعضای هیئت علمی گروه کودکان

بیمارستان مفید

|

تشخیص

بیماری گوشه

Gaucher Disease

Answer:

This nine-year-old girl, who had a long history of

epistaxis and hepatosplenomegaly, presented with acute leg pain.

Interestingly, a year earlier she had had similar leg pain, but it

had resolved without intervention. An important observation is that

the hepatosplenomegaly was chronic and probably progressive.

Pertinent features of the history include the absence of fevers,

trauma, scleral icterus, jaundice, weight loss, visual disturbances,

medications, and previous health problems. The results of the

physical examination are notable for the presence of low-grade fever,

mild systolic hypertension, marked hepatosplenomegaly, and tenderness

in the right thigh. The results of the neurologic examination were

normal, with no ocular motor abnormalities. Laboratory screening

revealed slight anemia, leukocytosis, low iron saturation, and a high

erythrocyte sedimentation rate, with minor elevations in the levels

of lactate dehydrogenase and aminotransferases. Cultures of blood and

urine were negative.

Abdominal ultrasonographic studies confirm the

presence of hepatosplenomegaly. A pelvic CT scan showed an effusion

in the right hip and patchy sclerosis in the left femoral epiphysis,

which suggested a previous episode of avascular necrosis.

MRI of the

pelvis and femurs was performed before and after the administration

of gadolinium. On T1-weighted images, the normal fatty

marrow of the pelvis and femurs is diffusely replaced by abnormal

marrow. The fatty marrow should have the same signal intensity as

subcutaneous fat, which appears as a bright stripe on this image.

Instead, it has the same signal intensity as muscle, indicating that

the bone marrow is affected by an infiltrative process. On a T2-weighted

image, there is edema in the marrow of the proximal right femur and

in the surrounding soft tissues; the scan obtained after the

administration of gadolinium shows diminished enhancement of this

region. These findings are characteristic of an acute bone infarct.

The distal femoral metaphyses are flared, an effect that is probably

due to the diffuse marrow infiltrate.

The two

central features of this case are chronic hepatosplenomegaly and

acute bone pain, which appears to be intermittent in nature. The

imaging studies suggest the presence of an infiltrative process in

the liver and the bone. I will consider the broad differential

diagnosis of hepatosplenomegaly and focus on disorders that can also

account for the bone findings, assuming that the hepatosplenomegaly

and the bone pain are the result of a single disease process. The

causes of hepatosplenomegaly can be sorted into broad categories that

include anatomical abnormalities, congestion, infection, hematologic disorders,

and infiltrative processes.

Several

specific anatomical entities, such as cysts, malformations, and

developmental anomalies, may result in hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, or

bone pain. However, these entities are usually regional and are not

likely to result in the constellation of findings that are present in

this case. Furthermore, most anatomical anomalies have characteristic

features on imaging studies, and such features are not apparent on

this patient's radiographic studies.

Passive

venous congestion can certainly cause long-standing

hepatosplenomegaly, which can be progressive. Congestion cannot

account for this child's bone pain, however, and furthermore there

are no additional signs of congestion, such as venous engorgement,

edema, stasis of the legs, or evidence of esophageal varices.

Infection

seems unlikely in this case for three reasons. First, although

several infections are known to cause either hepatosplenomegaly or

bone pain, it would be distinctly unusual for infection to cause both

of these clinical findings. Second, many infections tend to occur

over a relatively short period, whereas this child's organomegaly was

chronic. Third, most infections are associated with increased blood

flow, which would typically cause increased uptake rather than

decreased uptake on bone scanning.

Chronic

hepatosplenomegaly is a feature of several hematologic diseases,

including chronic hemolytic anemia, disorders associated with

extramedullary hematopoiesis, and myeloproliferative disorders.

Chronic hemolytic anemia usually causes hyperbilirubinemia, anemia,

and reticulocytosis, none of which were present in this case. In

addition, splenomegaly is usually more prominent than hepatomegaly in

chronic hemolytic anemia.

Sickle cell

disease deserves consideration, since this child's acute bone pain is

suggestive of a vaso-occlusive crisis. However, her medical history

includes no other manifestations of sickle cell disease, and this

disorder would not account for the progressive organomegaly.

Splenomegaly is a common finding in early childhood, but as children

approach their teenage years, it is very uncommon. Although

intrahepatic sickling may lead to some degree of liver enlargement,

it usually develops rapidly and typically is associated with evidence

of liver dysfunction.

Disorders

associated with extramedullary hematopoiesis, such as osteopetrosis

and myelofibrosis, may be associated with chronic hepatosplenomegaly,

but in patients with such disorders one would expect characteristic

findings in the peripheral blood and on the radiographs. Finally,

myeloproliferative disorders often lead to organomegaly, but they too

are associated with additional findings, such as marked abnormalities

in the peripheral-blood counts.

Infiltrative processes that cause hepatosplenomegaly and bone pain

include both malignant and nonmalignant conditions. Childhood cancers

associated with hepatosplenomegaly and bone pain include leukemia,

lymphoma, neuroblastoma, and primary hepatic tumors. Cancer seems

highly unlikely in this case simply because of the time course of the

patient's symptoms. Neoplasia in children usually takes the form of a

relatively acute process, with escalating symptoms over the course of

weeks or months rather than years. Despite this general observation,

it is important to consider briefly the specific malignant conditions

that could be relevant to this case.

Hepatosplenomegaly and bone pain are common findings in children with

leukemia; however, there are usually additional findings, such as

fever, an appearance of illness, and cytopenia.1

Lymphomas in children may cause hepatosplenomegaly, but they have

additional clinical features as well, such as fever, chills, weight

loss, and marked lymphadenopathy. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma is

a unique form of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma that may cause marked

hepatosplenomegaly without lymphadenopathy. However, this disease

typically affects young men, who present with prominent fever, weight

loss, and cytopenia.

Metastatic

neuroblastoma often involves both the liver and bones. This degree of

hepatomegaly in neuroblastoma is most commonly associated with stage

IV-S disease, which occurs exclusively in infants. In older children,

stage IV neuroblastoma may include both bone pain and hepatomegaly;

however, these children appear very ill, the bone involvement is

typically multifocal, and there is avid uptake of labeled technetium

on bone scanning. Hepatoblastoma may cause liver enlargement and may

metastasize to the bones, but this disease occurs almost exclusively

in children less than two years of age, and the vertebrae are the

usual metastatic targets.

Histiocytic

disorders that can occur in children include Langerhans'-cell

histiocytosis, non-neoplastic histiocytic disorders, including

familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and the infection-associated

hemophagocytic syndrome, and metabolic storage diseases. Langerhans'-cell

histiocytosis is a neoplasm of the Langerhans' cells that has

protean clinical manifestations. Common clinical findings include

lytic bone lesions, dermatitis, organomegaly, lymphadenopathy, fever,

weight loss, chronic otitis media, and diabetes insipidus.

Disseminated disease is seen in young children but is unusual at this

patient's age. The absence of these typical clinical findings, along

with evidence of a bone infarct, makes Langerhans'-cell histiocytosis

very unlikely. Patients with familial hemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis may present with infiltrative hepatosplenomegaly,

but most often they present (earlier in life than the child in this

case) with rapid clinical deterioration, including fever, wasting,

and skin rash, irritability, and central nervous system findings.

Likewise, the infection-associated hemophagocytic syndrome usually

follows a viral process, involves fever and pancytopenia, and usually

occurs in the setting of immunodeficiency, which does not seem to be

present in this case.

Hepatosplenomegaly is a common feature in many metabolic storage

diseases, ranging from sphingolipidosis to mucopolysaccharidosis. A

smaller number of metabolic disorders are associated with bone pain

or, as it is often called, bone crisis. The combination of

hepatosplenomegaly and bone pain is unique and is a feature of

Gaucher's disease. Gaucher's disease is a lysosomal glycolipid-storage

disease characterized by the accumulation of glucocerebroside

in various tissues as a result of a deficiency in the enzyme beta-glucosidase.

There are three forms of Gaucher's disease. The most common form,

non-neuronopathic (or type I) disease, involves the progressive

engorgement of macrophages over time, a process that results in

organomegaly, bone marrow infiltration, and damage to the bones,

which may lead to infarction or fracture. Children with this form of

Gaucher's disease are healthy in the first few years of life;

hepatosplenomegaly then gradually develops over the course of several

years. Splenomegaly is usually more prominent than hepatomegaly, but

there is notable heterogeneity in the clinical manifestations of

Gaucher's disease.

Bone involvement is present in nearly all patients and typically

occurs after visceral disease. The classic Erlenmeyer-flask

deformity, a common radiographic finding, is caused by medullary

expansion and remodeling of the distal femur due to the accumulation

of histiocytes. Patients usually have episodic, painful bone crises,

which have a predilection for the femoral head and sometimes are

misdiagnosed as Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease.

Erlenmeyer flask deformity of

the distal

These bone

crises result from ischemia and infarction due to progressive marrow

infiltration with enlarging storage cells. This patient's current

episode of leg pain, as well as the episode one year earlier,

represents a bone crisis that is fairly typical of Gaucher's disease.

Classic features of bone crisis in Gaucher's disease include fever,

leukocytosis, an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and

absence of tracer uptake on bone scans (i.e., "cold" bone scans).

Patients with Gaucher's disease are at increased risk for malignant

hematologic tumors that may cause bone pain, but such tumors tend to

occur much later in life and typically show increased tracer uptake

on bone scans.

In addition

to hepatosplenomegaly and bone pain, this patient had a three-year

history of epistaxis. Bleeding, particularly epistaxis, is common in

patients with Gaucher's disease and is usually the result of

thrombocytopenia due to hypersplenism. Qualitative defects in

platelet function and decreased levels of several coagulation factors

have also been described in patients with this disease.

This

patient probably has type I, or non-neuronopathic, Gaucher's disease,

since the rarer form — type II, or neuronopathic, Gaucher's disease —

is severe, involves the central nervous system, and occurs in young

children, who usually die by the age of two years. Type III, or

subacute neuronopathic, Gaucher's disease cannot be definitively

ruled out because neurologic signs may develop after symptomatic bone

disease. Ocular motor manifestations, which are typically the first

evidence of neurologic involvement, were not present in this case.

Gaucher's

disease can be diagnosed on the basis of a low level of beta-glucosidase

in peripheral-blood leukocytes. An alternative and more expeditious

diagnostic approach is bone marrow aspiration to search for classic

Gaucher's cells, which are very large macrophages with characteristic

morphologic features. With regard to clinical management, bony crises

typically resolve over the course of a few days with adequate

hydration and analgesia. Corticosteroids may also be beneficial.

Overall, this patient has an excellent prognosis and should be a

candidate for long-term enzyme replacement, which effectively

reverses the manifestations of Gaucher's disease and prevents

long-term complications.

Clinical Diagnosis: Gaucher's

disease.

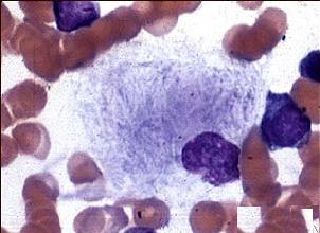

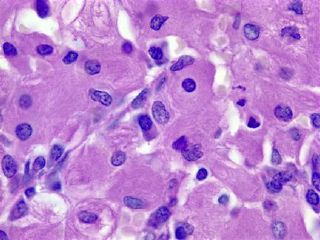

The

diagnostic procedure was bilateral bone marrow biopsy and aspiration

of the iliac crest. The tissue specimens retrieved from the two sites

had similar histologic features. The marrow contained solid sheets or

clusters of large cells or single large cells that displaced most of

the hematopoietic elements. These cells, with a diameter that was

about two to six times that of normal macrophages, contained

round or oval vesicular nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm

with a fibrillar or striated appearance. Wright–Giemsa staining of a

smear of aspirate also showed numerous large cells with striated

cytoplasm. These cells are histiocytes, and their large size and

fibrillar cytoplasm are characteristic of Gaucher's cells. The

differential diagnosis includes other metabolic storage diseases and

secondary accumulation of Gaucher's cells. The other major storage

disease to consider is Niemann–Pick disease. In that disorder, the

large histiocytes that accumulate have foamy cytoplasm with round

vacuoles, rather than a fibrillar or striated appearance. Gaucher's

cells — or pseudo-Gaucher's cells, as they are sometimes called — may

be found in persons without beta-glucosidase deficiency when

there is a very high rate of cell turnover. The classic setting for

this is chronic myelogenous leukemia, in which the presence of

increased numbers of hematopoietic-cell precursors in the marrow can

overwhelm the normal cellular machinery and result in the

accumulation of Gaucher's cells.

The

combination of the clinical findings and the morphologic features of

the bone marrow specimens from the iliac crest confirm that this

patient's diagnosis is type I Gaucher's disease. Gaucher's disease is

the most common of the genetic lysosomal storage diseases, affecting

1 in 50,000 to 100,000 live births; it can be inherited in an

autosomal recessive fashion or acquired through a spontaneous

mutation. Glucocerebroside, a normal component of the cell membrane,

is generated in macrophages as they degrade effete cells during

routine cell turnover. In the absence of beta-glucosidase,

glucocerebroside accumulates in the lysosomes of macrophages, where

it is stored in a specific architectural arrangement, resulting in

elongation of the lysosomes. These elongated and distended lysosomes

fill the cytoplasm of the macrophages, giving it the characteristic

fibrillar or striated appearance, which has been likened to wrinkled

cigarette paper.

Gaucher's cells